Liggi í úgildum akri — On Germanic bog burials

The burial of criminals in unhallowed ground, including in bogs, in Old Germanic sources and archæology

Abstract: This article begins with the titular formula (“may he lie in an unhallowed field”) in its context of the medieval Swedish Heathen Law, where it stipulates the burial of a man slain in a duel which he himself provoked through insult. I shine light on the meaning of this formula by comparing a number of older primary sources—written both by outsiders and by Germanic speakers themselves—relating similar practices in Old Germanic culture. I find that there is strong textual support in the sources for ritual disposal of criminals or other social deviants (so-called “nithings”) in unhallowed ground in Old Germanic culture. There is a particular association with bodies of water, and Norse pagan religious sources further suggest that these persons were thought to be tormented in a hellish watery afterlife. Finally I comment shortly on the relation between this textually attested cultural practice and the famous bog bodies of Northern Europe.

The “Heathen Law”

The Swedish “Heathen Law1” (Hednalagen) dates at least to the early C13th. While the original manuscript is now lost, two independent direct copies survive: The first written by C16th Swedish reformist judge and author Olov Persson2, the second by C17th Swedish scientist and historian Johan Bure3. The law and its copies have been excellently treated by the two great Swedish philologists Frits Läffler (1879) and Otto von Friesen (1902);4 it suffices to say that despite its late preservation, there are no doubts about its authenticity.

Due to the brevity of this law, I will here reproduce it in its entirety, mostly following Läffler’s edition, with a few minor changes according to von Friesen. The paragraph numbering is my own:

§ 1 Givr ·ᛘ· oquæþins orð manni. þu ær æi mans maki oc eig ·ᛘ· i brysti. Ek ær ·ᛘ· sum þv. þeir skvlv mötaz a þriggia vægha motum. § 2 Cumbr þan orð havr giuit oc þan cumbr eig þer orð havr lutit. þa mvn h’ vara svm h’ heitir. ær eig eiðgangr oc eig vitnisbær huarti firi man ælla kvnv. § 3 Cumbr oc þan orð havr lutit oc eig þan orð havr giuit. þa öpar h’ þry niþingx op oc markar h’ a iarþv. þa se h’ ·ᛘ· þæss værri þet talaþi h’ eig halla þorþi. § 4 Nv mötaz þeir baþir mʒ fullū vapnvm. Faldr þan orð havr lutit. gilder mʒ haluum gialdum. Faldr þan orð havr giuit. Glöpr orða værstr. Tunga houuðbani. Liggi i vgildum acri.

§ 1 ‘If a man gives (another) man a word of insult: “Thou art not the like of a man, and no man in thy chest!” — “I am (as much) man as thou!” They shall meet where three roads cross.

§ 2 If he comes who has given the word, and he comes not who has received (it), then he will be that which he was called: he may not swear oaths or bear witness, neither before man nor woman.

§ 3 And if he comes who has taken the word, and not he who has given (it), then he shouts three shouts of “nithing” and makes a mark in the soil. Then he is the worser man, who spoke that which he did not dare to hold.

§ 4 Now they both meet with full gear. If he falls who has taken the word; yauld5 with half gelds.6 If he falls who gave the word—a crime of words is the worst; the tongue the head’s slayer—may he lie in an unyauld field.’

Now, the point of this post is not to discuss the admittedly interesting Swedish dueling customs described in the law—rather, I wish to give support for a rare interpretation on the very last part, namely the title of this post, liggi í úgildum akri ‘may he lie in an unyauld field’.

In the Scandinavian legal corpus the adjective gildr ‘yauld’ often means ‘valued, compensated’, as indeed earlier in § 4: ‘yauld with (= valued at) half gelds’, the meaning being that the fallen man’s family receives a wergeld that is half of the regular. Following this, liggi í úgildum akri has been interpreted as equivalent to liggi úgildr í akri ‘may he lie unvalued in the field’, that is, without a wergeld paid to his family.

There is an obvious issue with this interpretation: it’s not what the text actually says. The renowned Carl Johan Schlyter7 addressed this concern in typically concise way: he brings up two passages with a similar expression, the first in the Law of the Westmen (Västmannalagen), regarding a thief who is slain after escaping and being caught (Þj. 3): liggi þęn í ógildum akri ok á verkum sínum ‘may he lie in an unyauld field and on (top of) his own deeds’, and the second in the Law of the Southmen (Södermannalagen), regarding a man who raids another’s home and is slain (Kg. 5:pr): liggi ógildr á verkum sinum ‘may he lie unyauld on (top of) his own deeds’.

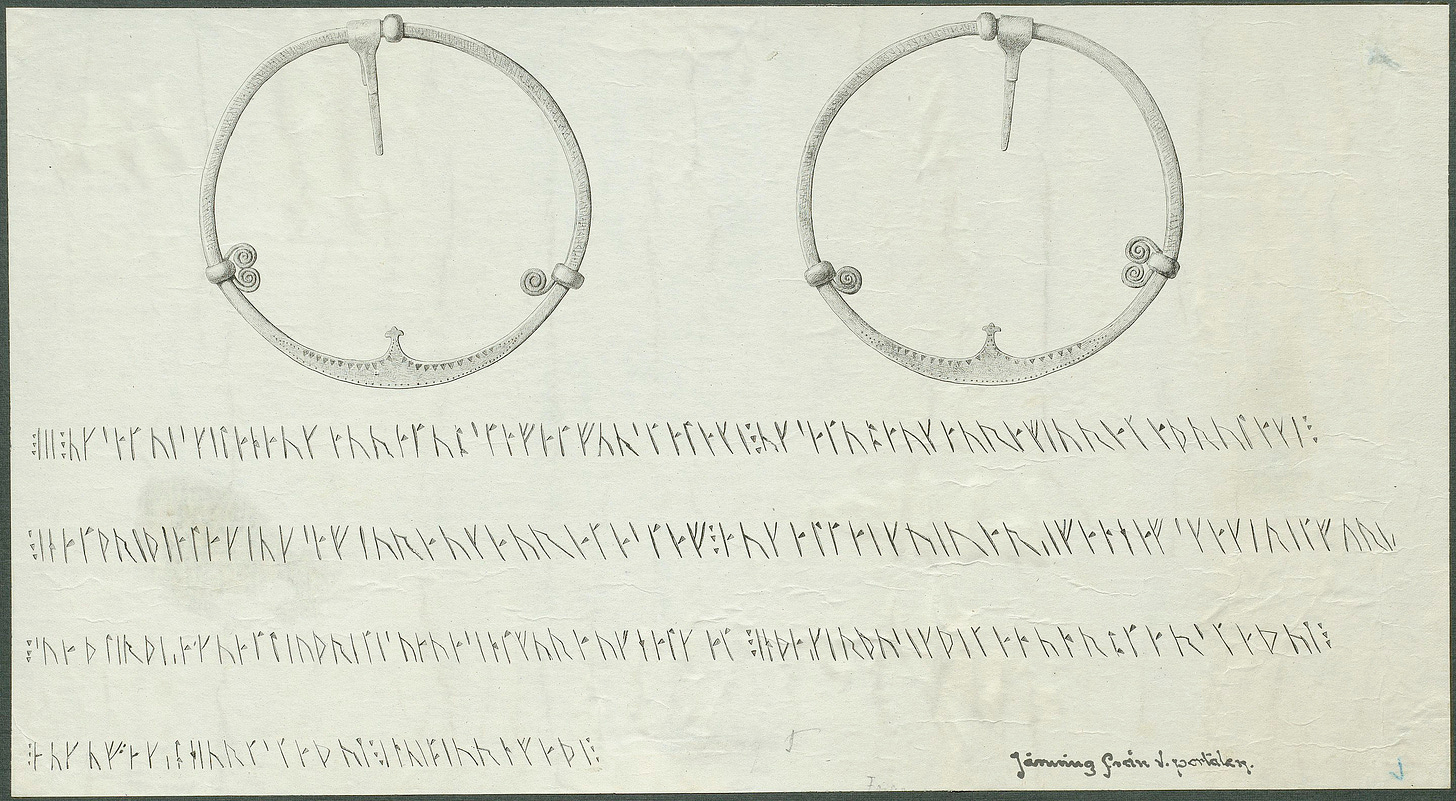

One might consider the matter settled here, but as I will try to show, the large legal literature suggests that the adjective ‘unyauld’ does in fact apply to the field, carrying a unique important sense. To figure out precisely unyauld what entails, we need to consult other Nordic legal sources. I will base my discussion around the Runic Forsa Ring (signum Hs 7).

The Forsa Ring

The Forsa Ring was set on the door of the medieval parish church of Forsa, Hälsingland and retrieved at its demolishing in 1840. It may originally have been from the neighbouring Hög socken, as that is where both of the places mentioned in the text are located. The text reads as follows (transliteration, normalisation and translation my own, paragraphs following the punctuation of the original):

¶ :|||: uksatuiskilanaukauratuąstafatfurstalaki : uksatuąaukaurafiurataþrulaki :

¶ : inatþriþialakiuksafiuraukauratastaf : aukaltaikuiuarʀifanhafskakiritfuriʀ :

¶ : suaþliuþiʀakuatliuþritisuauasintfuraukhalkat : inþaʀkirþusikþitanunrątarstaþum :

¶ : aukufakʀąhiurtstaþum : inuibiurnfaþi :§ 1 Oxa tuiskilan auk aura tvȧ8 staf at fyrsta lagi § 2 oxa tvȧ auk aura fiúra at aðru lagi, § 3 en at þriðja lagi oxa fiúra auk aura átta staf, § 4 auk allt ęigu í varʀ ef ’ann hafsk ękki rétt fyriʀ. § 5 Sváð liuþiʀ águ at liúð-rétti, svá vas innt fyrr auk hęlgat. § 6 En þęiʀ gerðu sik þetta: Anundr ȧ Tár-staðum, § 7 auk Ȯ·fęigʀ ȧ Heǫrt-staðum. § 8 En Ví-beorn fáði.

§ 1 ‘An ox tuiskilan and two ounces (ON. eyrir) staf at the first lay,

§ 2 two oxen and four ounces at the second lay,

§ 3 but at the third lay four oxen and eight ounces staf,

§ 4 and all of his property in seizure if he does not make right for himself.

§ 5 That which the liuþiʀ have for their people’s right, was suchwise spoken aforetime, and hallowed.

§ 6 And they made themselves this: Enwind (Anundr) on Tarstead (Társtaðir),

§ 7 and Unfey (Ȯ·fęigʀ) on Hartstead (Heortstaðir).

§ 8 And Wighbern (Víbeorn) carved.’

While the ring is wholly readable, there are a few controversies on its dating and interpretation, especially regarding the words liuþiʀ, tuiskilan and staf. The following is the traditional reading, partly represented by RunData and Bugge (1877):9

liuþiʀ has been transliterated as lirþiʀ (the u- and r-runes in the inscription are very similar), and read as masc. nom. pl. lirðiʀ ‘the learned (men)’. This word has been upheld as proof of the ring’s medieval providence, being as it is a post-Viking Low German borrowing.

tuiskilan has been read as masc. acc. sg. tvís-gildan ‘twice-yauld; doubly valued’, modifying oxa ‘ox’.

staf has been read as dat. sg. staf ‘the (Bishop’s) staff’, symbolically standing for the Catholic Church.

Following this, the inscription is interpreted as a medieval Catholic legal document. There are, however, several issue with this interpretation. As pointed out in a 1990 article by Bo Ruthström,10 several words are troubling: the prefix *tvís- is never attested in North Germanic (one would expect tví-), and staf, which occurs twice, is in both cases missing the dative singular ending -i. In spite of the supposedly medieval lirþiʀ, the runes are of a very archaic type, and even preserve the sequence -rʀ; they appear on the whole to belong the same stage of language as the C9th Rök stone.

The linguistic dating then conflict with the social structure required by the medieval interpretation, one that was hardly reached even in the C11th: there must have been a parish church with such close ties to the bishop that four oxen could be delivered to him, and Christianity must have been so established that a punishment like this could be effectively meted out. This is made worse by the inscription itself, which says that the law was innt fyrr auk hęlgat ‘spoken aforetime, and hallowed’, so that by the time of the carving it should already have been fairly old. Two internal contradictions are also present: First, while the fine systematically doubles, the first ox is supposed to be tvís-gildr, ‘doubly valued’, which in context scarcely makes sense. Second, while the law supposedly concerns Churchly matters, it is explicitly called liúð-rétt ‘(common) people’s right’!

What are we then to do with this? Ruthström offers an elegant solution to these problems, one that ties the Forsa Ring to the title of this post. To begin, the supposed medieval word lirþiʀ was shown by Aslak Liestøl (1979) to be liuþiʀ liúðiʀ, corresponding to Old Norse lýðir ‘common people’. Next Ruthström points out that the carver of the inscription—following common practice at the time, I should add—neglects to write the same rune twice in a row. Thus: § 2 fiurat is written for fiura at; § 3 fiurauk, aurata for fiúra auk, aura átta. With this rule in mind, he reads oxatuiskilan as oxa at vís gildan ‘an ox for the making yauld of the wigh’. This also solves the anachronism of a Catholic law: a wigh (Old Swedish ví, Old Norse vé) was a heathen sanctuary or shrine.

What does it mean that a wigh is to be made yauld? The wigh was, like the Christian churches, a place of frith (ON friðr)—that is, all violence was forbidden within. It could thus serve as a refuge even for wanted criminals, as attested e.g. in the C9th runic rock carving Ög N288 from Oklunda, East Geatland. In order for this to be applied, its boundaries must have been clearly delineated. This is seen both in the archeology: cultic sites are frequently surrounded by pole-holes, and literary sources: at Norse legal assemblies (so-called þing ‘Things’), the judges would sit within a space enclosed by cords or strings which were fittingly termed vé-bǫnd ‘wigh-bands’.

This rule of frith was continued by the church-yard (ON kirkju-garðr), in which compound the word yard means precisely ‘paled enclosure’. Heathen shrines could also be called yards, as seen e.g. in ch. 4 of the Gutnish Law, where men are forbidden from haita á […] hult eþa hauga eþa haiþin guþ, […] á wí eþa staf-garþa ‘calling upon thickets or mounds or heathen gods; upon wighs or staff-yards’.

Ruthström (p. 47 ff.) gives several examples from medieval Swedish laws where the word gilder ‘yauld’ and its antonym ó·gilder ‘unyauld’ refer to the state of a bridge, church-yard or fence being ‘valid, proper, satisfactorily maintained’. So the Law of the West-Geats (KB 13): é skal kirkju-garþer gilder varæ, báþi viter ok somar ‘A church-yard shall always be yauld, both in winter and summer.’

Using these examples, he explains gildan as a verbal noun corresponding to the rare verb gilda ‘to make yauld’, found once in the Dalian Law (BB 38:pr) regarding the upkeep of bridges: if a “yard or bridges” (garð ella bróar) are found to be “unyauld” (ó·gildar), “he who is responsible for making them yauld” (hann sum bró á gilda) must pay for the damage, along with a fine of three marks (= 24 aurar ‘ounces’, presumably of silver).

Bringing these threads together, the Forsa ring seems to refer to the upkeep of the enclosure to a heathen wigh, serving as a precedent to later laws regarding church-yards. This interpretation also explains the use word staff, which by the Gutnish compound staf-garþr is shown to have been used as the name for the poles enclosing a heathen wigh: depending on how many staffs (i.e. poles) have fallen down (at lagi staf), the fee, presumably imposed on the person responsible for its upkeep, is doubled. The significance of the fencing being yauld is likely ritual: if the wigh is not properly enclosed, it is no longer hallowed; even if only a single pole has fallen down.

With this we may return to the Heathen Law: the unyauld field is simply a field which is not properly enclosed. The fallen taunter is thus to lie in the wilderness, in unhallowed ground! This is strikingly similar to a passage in the Scanian Law (ch. 204): liggi utan kirkiugarþi, ofna ugildum akri ‘May he lie outside the Churchyard, on top of an unyauld field’.

Further literary parallels

There are numerous parallels to this custom in literature from across the Germanic world. Indeed, the earliest attestation of the practice is found already in Tacitus’ Germania, from ca. 98AD (ch. 12, ed. Latin Wikisource, tr. Church & Brodribb 187611):

Proditores et transfugas arboribus suspendunt, ignavos et imbelles et corpore infames caeno ac palude, iniecta insuper crate, mergunt.

‘Traitors and deserters are hanged on trees; the coward, the unwarlike, the man stained with abominable vices, is plunged into the mire of the morass, with a hurdle put over him.’

The oldest native Germanic text attesting something similar seems to be the shared curse formula found on the C6–7th Stentoften and Björketorp runestones from Blekinge province, southern Sweden.12 Originally, the two stones were each part of a respective heathen ritual monument, although only Björketorp remains in its original context.

Stentoften commemorates a sacrificial feast held by a local king and was originally surrounded by five uninscribed stones arranged in a pentagon; Björketorp still stands in a triangle together with two other uninscribed standing stones.

Although most differences between the two stones are simply linguistic13, Björketorp has some more words: it introduces its curse with uþArAbA sbA ú·þarba spǫ́ ‘prophecy of harmful things’ and adds the words uti aʀ úti eʀ ‘outside is’. This idea of a death “outside” fits well typologically. The inscriptions read as follows (my ed. and transl.):

Stentoften: […]14 herma-lausaʀ argjú, wéla-dauðé, sá þat briutiþ.

‘[…] Restless with degeneracy, in treacherous death, [is] he [who] destroys this [monument].’

Björketorp: ú·þarba spǫ́: argjú hearm-lausʀ, úti eʀ wéla-dauðé, sá’ʀ þat brýtʀ.

‘Prophecy of harmful things: With degeneracy restless, outside is in treacherous death, he who destroys this [monument].’

The second-oldest source is the C7th Law of the Frisians (Latin: Lex Frisionum), which at the very end contains a remarkable, unmistakably heathen paragraph. The context most closely parallels that of the Blekinge stones above—it is not impossible that a Germanic expression underlying fanum effregerit could have involved the root breut-; see note TODO. (XI.1, ed. and tr. by Dr. Kees C. Nieuwenhuijsen15):

Qui fanum effregerit, et ibi aliquid de sacris tulerit, ducitur ad mare, et in sabulo, quod accessus maris operire solte, finduntur aures eius, et castratur, et immolatur Diis quorum templa violavit.

‘If anyone breaks into a shrine and steals sacred items from there, he shall be taken to the sea, and on the sand, which will be covered by the flood, his ears will be cleft, and he will be castrated and sacrified to the god, whose temple he dishonoured.’

The breaking of shrines16 is also mentioned earlier in the law, regarding hominibus qui sine compositione occidi possunt ‘people that can be killed without a fine’ (V.1):

Campionem; et eum, qui in praelio fuerit occisus; et adulterum; et furem, si in fossa, qua domum alterius effodere conatur, fuerit repertus; et eum, qui domum alterius incendere volens, facem manu tenet, ita ut ignis tectum vel parietem domus tangat; qui fanum effregit; et infans ab utero sublatus et enecatus a matre.

‘The duellist, who is killed in combat; and the adulterer and he who is caught in a ditch, through which he is undermining the house of another; and he who attempts to set fire to the house of another, who has the torch in his hand, while the flames reach the roof or wall of the house; he who demolishes a shrine; and the child expelled from the womb that is strangled [or: killed without nutrition] by the mother.’

The mention of the duellist in this paragraph also connects it to the Swedish Heathen Law above. Further, the prescribed punishment is remarkably similar to one found in the C12th Law of the Gole-Thing (ON Gula-þings-lǫg) from Norway (ch. 23, my ed. and tr.):

Þat er nú því nę́st at mann hvern skal til kirkiu fǿra, er dauðr verðr, ok grafa í jorð helga—nema ú-dáða-menn: dróttins-svika ok morð-varga, trygg-rofa ok þjófa, ok þá menn er sjalfir spilla ǫnd sinni. En þá menn, er nú talda ek, skal grafa í flǿðar-máli, þar sem sę́r mǿtisk ok grǿn torfa.

‘It follows next that each man who dies shall be brought to the church, and buried in hallowed ground—save for men of misdeeds: traitors to their lord17 and murder-wargs18, truce-breakers and thieves, and those men who themselves destroy their spirit19. But those men which I now listed shall be buried in the flood-mark where sea and green turf meet each other.’

Of particular note is the word morð-vargar ‘murder-wargs, men outlawed for murder’, which also occurs in the C10th Norse Spae of the Wallow (ON Vǫlu-spǫ́) in a description of afterlife punishment (my ed. and tr., sts. 37, 38):

Sal sá hǫ̇n standa · sólu fjarri

Ná-strǫndu ȧ, · norðr horfa dyrr;

falla ęitr-dropar · inn umb ljóra,

sá ’s undinn salr · orma hryggjum.‘A hall she saw standing far from the sun

on Neestrand (‘Corpse-shore’)—north face its doors.

Venom-droplets fall in through its smoke-vent,

that hall is enwrapped by the spines of snakes.’Sá hǫ̇n þar vaða · þunga strauma

męnn męin-svara · ok morð-varga

ok þann’s annars glępr · ęyra-ru̇nu.

Þar saug Níð-hǫggr · nái fram-gingna;

slęit vargr vera. · Vituð ér ęnn eða hvat?‘There she saw wading through heavy streams

perjurious men, and murder-wargs,

and the one who seduces another’s ear-whisperer [WIFE].

There sucked Nithehewer from corpses passed-on,

the warg tore men asunder.—Know ye yet, or what?’

Regarding these two stanzas I wish to propose a hypothesis which I’ve not seen mentioned previously, namely, that they depict the afterlife of criminals buried in unhallowed ground, specifically bogs and flood-marks. After death the burial marshes would then transform into the þungar straumar ‘heavy streams’ which the deceased had to wade through. At this point it might not surprise the reader that the crimes listed in the stanza (viz. perjury, murder, and adultery) are very much like those mentioned in the previously cited sources.

Also of note is the monstrous tormenter Nithehewer (ON Níð-hǫggr), whose name transparently means ‘Nithe-striker’. nithe ‘shame, hatred’ is also the first element of nithing ‘one afflicted with nithe’, a term used for certain shameful criminals in early English and Nordic law, including in the Heathen Law above. It is sensible that such nithings should be tormented in the afterlife by a Nithe-striker. (Perhaps this nithe was even thought of as a semi-physical substance, which the dragon would “suck” out of the dead criminals? This may have support in the well known curse ritual of the nithe-pole, where the curser would ritually declare that he was sending nithe in the direction of his enemy.)

One of the crimes listed in Vǫlu-spǫ́ 38 above is perjury.20 We can compare two stanzas from the Eddic poem Regins-mǫ́l, which clearly attest an afterlife punishment involving wading for the crime of perjury (my ed. and tr.):

Sęg-ðu þat, And-vari, (kvað Loki) ef þú ęiga vill

líf í lýða sǫlum:

Hvęr gjǫld · fáa gumna synir

ef þęir hǫggvask orðum á?‘Say that, Andware—quoth Lock—if thou wilt have

life in the halls of men:

Which recompense do the sons of men get,

if they hew at each other with words?’Ofr-gjǫld · fáa gumna synir

þęir’s Vað-gęlmi vaða;

ó·saðra orða · hvęrr’s á annan lýgr,

of lęngi lęiða limar.‘Overwhelming recompense do the sons of men get,

those who wade in Wadyelmer.

By the ramifications of untrue words is every man

who lies to another long followed.’

Relevant is also this less straight-forward stanza of advice from the Eddic poem Sigr-drífu-mǫ́l (my ed. and tr.):

Þat rę́ð’k þér annat · at ęið né svęrir

nema þann’s saðr séi;

grimmar símar · ganga at tryggð-rofi,

armr er vára vargr.‘I counsel thee secondly: that thou swear no oath,

save for one which is true.

Grim [fate-]strands21 go against the truce-breaker;

wretched is the warg of vows [= oathbreaker].’

Another relevant Eddic poem is Guð-rúnar-kviða III. In this short poem the handmaiden Harch (ON Hęrkja) accuses king Attle’s (Atli) wife Guthrun (Guð-rún) of adultery. The dispute is settled by a brutal trial of ordeal, wherein both women have to take a gem out of boiling water with their bare hands. Guthrun is redeemed, but Harch is not so lucky. She is drowned in a fúl mýrr “foul bog”, as described in the hauntingly concise final stanza (st. 10, my ed. and tr.):

Sá-at maðr armligt, · hvęrr es þat sá at,

hvé þar á Hęrkju · hęndr sviðnuðu;

lęiddu þá męy · í mýri fúla,

svá þá Guðrún · sinna harma.‘No man looked on with pity, of those who saw it:

how there on Harch the hands were scorched.

They led that maiden into the foul bog;

thus was Guthrun reconstituted for her affronts.’

Bog bodies

I have shown that there is strong and varied textual support for the disposal of criminals in unhallowed ground (with a particular association with water) in early Germanic culture, such that it is found in:

Roman ethnographical writing like Tacitus’ Germania,

Germanic law codes like the Law of the Frisians, the Heathen Law, and the Law of the Gole-Thing,

Runic inscriptions like the Björketorp runestone,

and Norse Eddic poetry like the Vǫlu-spǫ́, Ręgins-mǫ́l and Guð-rúnar-kviða III,

In the face of such varied evidence, it seems clear that the sources must reflect a real-world practice. Of most weight are the law-codes, since they must, at some point, have been applied.

If we are to look for these unhappy criminals in the archeological record, the obvious choice is surely the large number of bog bodies found in marshes in northern Europe. These bog burials date from several millenia, and may have meant different things to their respective communities—some of those buried may have been the unfortunate victims of highwaymen, or ritual sacrifices outside of a criminal context. Still, it seems overwhelmingly likely that, at least in the 1st millenium AD, some of them were ritually executed for actions viewed as deeply shameful by their own communities, and consigned to wade through the heavy streams of the bog or flood-mark, until they were at last dug up by industrious peat-diggers in the last few centuries.

Of particular importance are those bog burials which Swedish archeologist Sandklef22 calls “Tacitus finds”, after the passage from Germania. In these finds the victim has been drowned in the bog rather than slain beforehand—sometimes through an elaborate method: the victim has been fettered with yokes over knees and elbows and thrown into a dugout in the bog, and then left to drown as the water level rose. This directly parallels the burial in flood-marks at low tide in the two Norwegian and Frisian laws quoted above. Sandklef understands the purpose of the ritual as self-preservation on the part of the executioners: by letting the water drown the victim, rather than slaying him directly by their own hands, they shield themselves from eventual curses or other types of supernatural retribution.

Edits: Nov 2023: Added links to Ruthström and Bugge’s articles. — 7 Dec 2023: Rewrote the first part and added numerous new citations. — 14 April 2024: Fairly substantial rewrite, added final section on bog bodies. — 18 June 2024: minor fixes, added note about the Germanic glosses of fānum and their associations. — 23 Oct 2024: Add reference to Sandklef, improve abstract.

The name derives from a historical note found preceding the fragment in Bure’s 1607 edition (see note 3 below):

Af thöm gamblu Laghum sum i hedhnum tima brukadhus, vm kamp ok enwighe.

‘From the old laws which were used in Heathen time, about fighting and duelling.’

This note is written in C14–15th Swedish, and can therefore not have been added by Bure himself; it was probably written in the margins of the now-lost original C13th manuscript. It also seems to have inspired Olov Persson to write the following in his Swedish chronicle:

Thenna laghen som aff hedendoomen är kommin, haffuer en tijdh lång wordet brukat sedhan Christendoomen kom hijt i landet, Ty ståår hon och i the äldzsta laghböker, som finnas

‘This law, which has come from Heathendom, has been used for a long time since Christendom came to this land. Therefore it also stands in the oldest law books that may be found.’

Commonly known by the latinised form Olavus Petri. The copy is found in his Swedish Chronicle, completed around 1523.

Again, commonly known as Johannes Bureus. The copy is found as an appendix to his 1607 printed edition of the medieval Swedish Upland Law.

Respectively in Om den fornsvenska hednalagen (1879) and Olavus Petrus egenhändiga avskrift av den s.k. Hednalagen i Ängsöcodex af Upplandslagen (1902), both of which are available for free on Swedish Wikisource.

As we try to find out its precise meaning, I will render Old Norse gildr by its direct English cognate, yauld.

Payments, fees; cognate with the second element in wer-geld ‘man-payment’.

Inspired by the First Grammarian I use a dot to reflect the nasal quality of the vowel, written ᚭ (usually transliterated as ą) in the inscription.

ANF 105:41–56: Forsa-ristningen — vikingatida vi-rätt?

From English Wikisource.

This curse has several younger parallels in the Norse world, for which I plan to make a separate post.

The Björketorp stone looks to be a few decades younger, displaying more progressed syncope of unstressed vowels. It also has the North Germanic merger of the 2nd and 3rd present indicative singular in verbs, leading to Björketorp bArutʀ brýtʀ ‘breaks, destroys’ vs. Stentoften bAriutiþ briutiþ ‘id.’.

Apart from the curse, the Stentoften stone also contains a dedicatory formula wherein a local ruler celebrates the sacrifice of eighteen male animals for the sake of the harvest. The animals were presumably eaten as part of a large feast, which also involved the raising of the monument.

The Latin word used in both passages is fānum, which is decidedly non-Christian. It is glossed in Old High German as ab·got ‘idol’, ab·got-hús ‘idol house’, bluoz-hús ‘bloot-house’, and harug ‘outdoor ritual site’ (Lateinisch-germanistisches Lexikon, Köbler 1975:161). The first two terms are clearly derogatory—ab·got is literally ‘offgod’, i.e. ‘false, deviant god’—but the latter two are of native Germanic extraction, and find cognates in other Germanic languages, viz. ON blót-hús and hǫrgr, also OE hearg, whence modern English harrow (not to be confused with the agricultural tool).

In Scandinavia reflexes of hǫrgr are fairly common in place names, and the term is used positively in Norse pre-Christian poetry; it is also glossed with fānum in Stjórn, and is paired with blót-hus in Rekstefja 9, where it is said of the late king Anlaf Trueson (ON Ǫ́láfr Tryggvasonr) that he would láta brenna firna mǫrg blót-hús ok hǫrga ‘let a great many bloot-houses and harrows be burned’. In England hearg occurs in place names (e.g. in Harrow, London), and in Beowulf 175 it is said that the Heathen Danes ge·héton æt hærg-trafum ‘called upon harrow-tents(?)’.

An interesting expression in ON is brjóta hǫrg(a) ‘break (a) harrow(s)’, found both in laws and in the kings’ saws. So, in another poem, the above-mentioned king Anlaf is called a hǫrg-brjótr ‘harrow-breaker’. brjóta is also used on the Stentoften and Björketorp stones (see above), and there may thus be reason to guess that the full Germanic phrase underlying the Frisian Law’s fānum effregerit ‘breaks a harrow’ be something like Proto-Germanic *harugą briutidi.

I had earlier translated dróttins-svika acc. pl. as ‘betrayers of the Lord’, but this is false. ONP gives dróttins-sviki as meaning ‘traitor to one’s lord/master’, and this sense also fits much better in context.

In a legal context ON vargr (by me rendered as English warg, though the phonologically expected form would perhaps be **warrow) means ‘outlaw’, specifically one who can be murdered with impunity due to the severity of his crime. A morð-vargr “murder-warg” is then a man outlawed for murder.

sjalfr spilla ǫnd sinni ‘destroy one’s own spirit; commit suicide’. This is probably included in the list due to the Catholic Churchly taboo against suicide (something unknown in earlier pre-Christian sources). This may cast doubt on the value of this passage for knowledge of Old Germanic law. I see two counterpoints to that: First, the other listed crimes are similar in nature to those found in the other listed sources, including the pre-Christian Roman Germania and the Norse Heathen Vǫluspǫ́. Second, the punishment of burial in a flood mark is to my knowledge never prescribed in Church Law; it rather, again, agrees with non-Christian sources.

I plan to write a dedicated article on native Germanic ideas of divine punishment for swearing false oaths, something which—for now suffices to say—is well attested in the sources.

ſımar ‘strands’ as found in the Codex Regius, could easily be a copying mistake for an original *lımar ‘ramifications’

Sandklef 1944: De germanska dödsstraffen, Tacitus och mossliken. I was not aware of this article when I first wrote the present post; but I feel encouraged by the similarities in our argumentation.