[Part 1] The significance of the Germanic j-rune and its name

Some notes on the meaning and pre-Christian use of *jērą ‘year; harvest’

1. Introduction

The Proto-Germanic name of the j-rune, the oldest shape of which is ᛃ, is traditionally reconstructed as *jērą1. Very often, this word is simply translated by its direct English descendant, ‘year’, and that sense most likely did exist in the Proto-Germanic period, as it is present in all modern Germanic languages. The goal of this post, however, is to show using primary sources that the quick cognate-translation of ‘year’ is not wholly accurate, and that the word year, in Old Germanic, could also mean ‘fruitful harvest, plenty, prosperity (of crops)’; further, I will discuss its potential significance in the pre-Christian Germanic worldview.

2. Runological principles

Before I delve into the primary sources, I have to explain two important factors of runology, namely the acrophonic principle and the ideographic use of runes. I assume that the reader already knows that runes are the earliest Germanic writing system, and that each rune has a name consisting of a single noun.

2.1. The acrophonic principle

An important aspect of the names of the runes is that they follow the acrophonic principle. This really just means that the name of each rune, with one exception2, always begins with its sound value. Thus the name of the h-rune (Elder Futhark ᚺ, Anglo-Frisian fuþorc ᚻ, Younger Futhark ᚼ) is in Old English hægl, in Old Norse hagall, both meaning ‘hail’. This is not a Germanic invention. Like the alphabet itself, it originates with the Phœnicians, among whom the letter a was, for instance, called ʾālep ‘bull, ox, head of cattle’, the letter b, bēt ‘house’, &c. (These terms are, of course, the origins of the Greek letter-names alpha and beta.)

In runology this principle has some interesting effects, in that it often seems to work backwards—that is, when the first sound in the rune’s name undergoes some change, its sound value changes accordingly. This is seen in the j-rune. When /j/ was lost before vowels in late Proto-Norse, the name of the rune ᛃ (the shape of which had at that point become ᛡ) changed from *jāra to *āra. This in turn lead to the rune’s sound value changing from /j/ to /a/, and, with the loss of one diagonal stroke, giving us the attested Old Norse rune ᛅ ár. Since the name of the old a-rune ᚨ had gone from Proto-Germanic *ansuz to something like *ãsuʀ, the first vowel now a long nasal, its sound value was narrowed to represent only a nasal /ã/, in contrast to the oral /a/ represented by ᛡ ~ ᛅ. Interestingly, both of these developments had been completed by the time of the Stentoften stone, for which see below.

2.2. The ideographic use of runes

Runes could and often were used ideographically, that is, to stand for or abbreviate their names. This custom continued even into Latin-script manuscripts in vernacular Germanic languages. In Old English manuscripts numerous runes are used in this way, e.g. in line 520 of Beowulf, where the rune ᛟ stands for éðel ‘ancestral turf, homeland’ (fig. 1):

þǫnǫn hé ge·sóhte · swę́sne ᛟ [= éðel]

‘from there he sought out his beloved homeland’

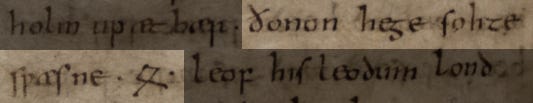

Likewise, the rune ᛘ, deriving from earlier ᛗ, frequently stands for its name maðr ‘man’ in Old Norse manuscripts, e.g. in the first half of st. 23 of the Háva mǫ́l (fig. 2):

Ó·sviðr ᛘ [= maðr] · vakir um allar nę́tr,

ok hyggr at hví-vetna‘the unwise man is awake every night,

and thinks about anything’

3. The rune poems

The traditional names of the runes and their meanings are foremost known to us from three old rune poems, all of which follow the same format: for every letter in their respective runic alphabet3, they give the name followed by a poetic description of the thing the name represents (e.g. ᚱ “riding”, ᚺ “hail”, ᛗ “man”). In chronological order, the main rune poems are the English, the Icelandic, and the Norwegian. Aside from its being the oldest, the English rune poem is important in showing that the naming of the runic letters is not a “Norse”, Wiking Age innovation, but rather goes back to the early Germanic period.

3.1. The Anglo-Saxon rune poem

In the Anglo-Frisian Fuþorc, the reflex of ᛃ *jērą is ᛄ gér4. For this rune the English rune poem reads:

Gér byþ gumena hiht, · þonne God lę́teþ,

hàlig heofones cyning, · hrusan syllan

beorhte bléda · beornum ond þearfum.‘Year is men’s hope, when God makes—

the Holy King of Heaven—the ground give up

bright blossoms, for warriors and paupers [alike].’

3.2. The Norse rune poems

In the Younger Futhark, the reflex of ᛃ jērą is ᛅ ár. For this rune the Icelandic rune poem reads:

Ár es gumna góði · ok gótt sumar

al-gróinn akr.‘Year is men’s goodness, and a good summer,

[and] a fully grown acre.’

For the same rune, the Norwegian rune poem reads:

Ár es gumna góði; · get’k at ǫrr vas Fróði.

‘Year is men’s goodness; I recall that Frood was generous.’

The reference to Frood (ON Fróði ‘the Wise’) here is probably due to the common collocation ár ok friðr ‘year and frith’, that is, ‘plenty and peace’5. Frood was a legendary Danish king famed for his generosity and for his peaceful reign, for which he earned the nickname Frið-Fróði ‘Frith-Frood’.

4. Earlier runic inscriptions

Having seen that the reflexes of ᛃ *jērą in the rune poems carry the meaning of ‘harvest’ rather than ‘calendrical year’, and that runes can be used on their own to stand for their meanings, we can now discuss the two Runic, pre-Christian instances of ᛃ being used in this way.

4.1. The Stentoften runestone

The first inscription we will look at is that of the C6–7th Stentoften runestone (signum DR 357).6 This stone is actually the younger of the two relevant inscriptions, but I discuss it first since it is such an indisputable attestation ideographic ᛃ. I will only quote the first three lines of it (fig. 3), as they are the ones relevant to this post.

ᚾᚢᚺᛡᛒᛟᚱᚢᛗᛦ ¶ ᚾᛁᚢᚺᚨᚷᛖᛋᛏᚢᛗᛦ ¶ ᚺᛡᚦᚢᚹᛟᛚᛡᚠᛦᚷᛡᚠᛃ […]

niuhᴀborumʀ ¶ niuhagestumʀ ¶ hᴀþuwolᴀfʀgᴀfj […]níu haβᵒrumʀ,

níu hangistumʀ,

Haþuwolᵃfʀ gaf ᛃ [= ár].‘Through [the sacrifice of] nine bucks,

through [the sacrifice of] nine stallions,

Hathwolf gave a (good) harvest.’

The import of the above section is clear: Hathwolf, surely an important chieftain or petty king, sacrificed 18 male animals7 (to the Gods) in order to guarantee a fruitful harvest, here expressed ideographically with the ᛃ rune. He then commemorated the sacrifice (which was most likely tied to a large communal feast, where the meat of the animals was eaten) by raising the stone.

An interesting linguistic note, with regard to the ideographic use of the ᛃ rune on the Stentoften stone, is that a younger variant of the same rune, ᛡ, is used to stand for oral /a/.8 This is a curious type of digraphia, since the younger variant of the rune is used for writing the sound it actually stands for, while the older variant is used for its ideographic meaning. The closest runic parallel I can think of is in the Geatish Ingelstad inscription (signum Ög 43) written in the Younger Futhark, where the by-then obsolete Elder Futhark d-rune ᛞ is, however, still used to stand in for its name “day” (or rather the male given name Day).

4.2. The Skodborghus-B bracteate

The second inscription featuring ideographic ᛃ is the older C5–6th Skodborghus-B bracteate (signum IK 161). The full inscription (fig. 4), with spaces inserted for clarity, reads:

ᚨᚢᛃᚨ ᚨᛚᚨᚹᛁᚾ ᚨᚢᛃᚨ ᚨᛚᚨᚹᛁᚾ ᚨᚢᛃᚨ ᚨᛚᚨᚹᛁᚾ ᛃ ᚨᛚᚨᚹᛁᛞ

auja alawin auja alawin auja alawin j alawidauja Alawin, auja Alawin, auja Alawin, ᛃ [= jāra] Alawid

luck for Alawin, luck for Alawin, luck for Alawin, prosperity for Alawid

The transparent structure of the text makes it clear that the rune ᛃ is expressing something similar to the runic charm word auja ‘luck, fortune, (personal) success’.9 The most reasonable reading, then, is that it is standing for its name *jāra like on the Stentoften stone. The whole inscription may then be read as a kind of mantra meant to bring fortune, or auja and jāra, to the addressees.

———

Having looked at the Runic sources, I will in the next part further discuss the significance of the word “year” itself, along with its relation to pre-Christian Godly Kingship and especially the Swedish monarchy.

This reconstruction is very secure. The j is attested in all old daughter languages except Old Norse ár, where word-initial j- is regularly lost. It is also shown by the rune’s sound value, /j/ (following the acrophonic principle; see above), which is present even in older North Germanic inscriptions, like the inscribed Gallehus horn. The ē (which itself derives from a Proto-Indo-European *e assimilating a following laryngeal *h₁) is retained in Gothic jēr, but regularly becomes -ā- in Northwest Germanic, where it is later fronted into ǣ or ē in Old English, Old Frisian and Old Saxon. Lastly, the ending -a in the nominative/accusative singular of neuter a-stems is attested in Proto-Norse inscriptions. The only uncertainty is the nasality, since earlier Proto-Norse does not distinguish between nasal /ã/ and oral /a/, and, by the time it does, the final a-vowel has been syncopated (as it likewise has in all the other attested Germanic languages, including Gothic). We know that the neuter a-stem ending must have been nasal at some point, since it descends from PIE *-om, but whether it was still nasal or oral in Proto-Germanic is thus unclear.

Namely the z-rune, as /z/ did not occur word-initially in Proto-Germanic. The original name of the rune is uncertain, as the Norse and English traditions conflict. By the time the English rune poem was composed, /z/ had in that language merged with /r/, and the old rune was repurposed to stand for /ks/, having the name eolhx ‘elk’. In Old Norse the rune was called ýr ‘yew’, which, however, corresponds to the name of the rune ᛇ eoh in Old English.

While all the Runic alphabets descend from the same now-lost original and share many traits in common (namely the names and shapes of many runes, and the sequence f, u, þ, a, r, k &c. rather than the Phœnician a, b, &c.), they do vary slightly. The Old English rune poem describes the Anglo-Frisian Fuþorc, which is essentially an expanded version of the earliest runic alphabet, the Elder Futhark. On the other hand the Icelandic and Norwegian rune poems both describe the Younger Futhark, essentially a shortened version of the EF. Luckily for our purposes, reflexes of the j-rune are present in all three futharks.

This is the spelling of the word in the preserved printed copy of the Rune poem, in West Saxon Old English it would instead be spelled geár. In both cases, the written <g> represents the sound /j/.

This collocation itself has religious significance and is closely connected to the idea of Godly Kingship. I will discuss it further in the next part.

I have translated another part of the Stentoften inscription in my post titled Liggi í úgildum akri, where I discuss bog burials.

The sacrifice of male victims in multiples of nine is also attested in Adam of Bremen’s account of the Temple of Uppsala.

For the use of the ᚨ rune to represent exclusively nasal /ã/ see above under the acrophonic principle!

auja is probably from Proto-Germanic *awją (the only real difference between this and the attested Proto-Norse form is of orthography), from the same root as PGmc *auþuz ‘easy’. The literal meaning is thus something like ‘that life becomes easy for you’. — Other attestations are on the C5th–6th Seeland bracteate (signum IK 98): ᚷᛁᛒᚢᚨᚢᛅᚨ gibu auja ‘I give fortune’, and in an archaic prayer to the Christian Cross recorded in the C12th Icelandic Book of Land-takings (ON Land-náma-bók): gótt ęy gǫmlum mǫnnum, gótt ęy ungum mǫnnum ‘good fortune to old men, good fortune to young men’.

Excellent reading. Thanks so much, and I am looking forward to the next part.

I'm not saying that the bucks and stallions are the objects of the verb "to give", the object is clearly "year".